Sustainability

Risky Business

Sustainability is a key focus for many industries and not a moment too soon. Hopefully, not a moment too late. Infrastructure needs to be sound to survive the effects of climate change and this goes for private banking infrastructure as well. Hannah Wright writes.

A

s the last month of winter in Texas, February is typically mild. With temperatures up to 18°C and a relative humidity of 70%, it’s the type of temperature that would prompt many Brits to pull on a pair of shorts. Except this year, Texas has been battered by climate change. Enduring power shortages and paralysed water systems, the region’s infrastructure has crumbled under the growing stress of the extreme winter weather, attributable to the climate crisis.

A few weeks earlier, 165 miles south of San Francisco, California’s Highway 1 collapsed after a severe rainstorm triggered a landslide, creating a 150ft fissure along the scenic highway which hugs the Big Sur coastline. The road, which spans 656 miles, has reportedly remained partially closed since it the year it opened, due to persistent issues arising from coastal erosion and rising tides.

As the climate crisis brings more frequent and intense weather our infrastructure is failing and with it, a wave of other unpredictable disruptions across industry and broader society.

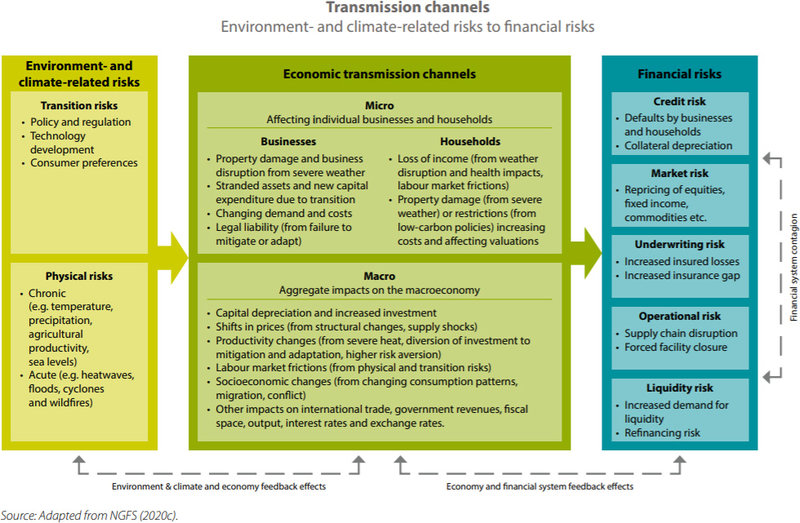

In the financial industry, climate risks have finally arrived at the top of the agenda, and the responsibility of institutions to act is real and recognised. Every economic figure is affected by environment related risks. Through various loan-related activities, banks are exposed to several sectors vulnerable to the risks – both physical and transitional - of climate change.

Speaking to PBI, Chris Kaminker, head of sustainable investment research and strategy at Lombard Odier, explains: “The climate crisis is already material to risk today and is going to become a dominant driver of risk and returns in the near term.”

Chris Kaminker Lombard Odier

Resulting from meteorological and climatological events, physical risks have a direct impact on people and goods. Physical risks can be chronic, such as rising sea levels, which cause the deterioration of the productivity of a given sector.

Alternatively, they are associated with extreme weather events and the damages incurred, such as the destruction of physical assets, as seen in the case of Texas. Transitional risks, on the other hand, arise in response to the implementation of energy policies or technological changes aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Embracing the opportunities amidst the chaos, Kaminker believes the transition to a green economy could represent the largest wealth creation event in our time, but also one of the largest value destruction events.

“It is Schumpeterian in nature,” he adds. “We are already seeing this value destruction in fossil fuel firms and other legacy industries.”

However, climate risk is poorly understood, and if industries are to capitalise on any wealth creation, this cannot be the case. Climate risk assessment involves identifying, evaluating, monitoring, and reporting on climate risks.

According to Deloitte, the current risk methodologies used by financial institutions – such as ESG data, carbon footprint approaches, and sector policies - are inadequate. In its report, The Predictive Power of Stress Tests to Tackle Climate Change, Deloitte clarifies the approach that we ultimately need, but don’t currently have: “The irreversible nature of climate change requires the creation of a comprehensive climate risk assessment approach.”

Insufficient, inadequate, occasionally inaccurate

Building on the inadequacies of the current risk assessment tools one at a time, Kaminker explains: “Traditional ESG data is insufficient to understanding the nature of the change that is underway. We’ve been working with ESG data for 30 years, and it is a good metric, but it does not equate to sustainability; it is not the be all and end all solution. ESG focuses on business practices, such as the policies and safeguards that a company may have in place. It doesn’t tell you much, if anything at all, about the business model of a company or how poorly positioned that firm is for a sustainable future.

“Many oil and gas companies have strong ESG scores because it is only looking at how they operate. ESG data, in this case, doesn’t tell you anything about whether oil demand will collapse in the face of renewables.

“Carbon footprint is an important metric, but it doesn’t always cover the entire lifecycle of emissions. If you’re not looking at scope 3 emissions, the exercise is a complete waste of time. Indeed, it could be deeply misleading.”

Scope 3 emissions are the result of activities from assets not owned or controlled by the reporting firm, but that the organisation indirectly impacts in its value chain.

Kaminker continues: “For industries like oil and gas, or automotive, most emissions fall within the scope 3 category. If you only look at a company’s direct emissions, then you’re only seeing part of the picture. The automotive industry was the first to get regulated on downstream scope 3 emissions and the others will come. At Lombard Odier we can compute a company’s carbon footprint, including scope 3. We compute this metric for over 20,000 firms across multiple geographies.

Carbon footprint has been used to decarbonise indices and portfolios but that pushes out all the high carbon industries.

“Unfortunately, even that is not the full picture. It tells you how big the problem might be – it is the altitude at which a company is flying. Carbon footprint has been used to decarbonise indices and portfolios but that pushes out all the high carbon industries. We need these industries, but we also need them to decarbonise. You cannot switch off agriculture, glass, cement, oil, long distance transportation, and plastics overnight. They need to transition. Carbon footprint tells us how material the problem is, but it doesn’t tell us whether the company is doing anything about it, and that’s what we want to know. That’s why forward-looking data is crucial.”

A key component of forward-looking climate risk assessment, stress tests analyse how portfolios behave under various hypothetical macroeconomic scenarios of the future and are formed by a series of assigned variables.

A typical stress test includes a scenario, accompanied by a covering narrative, a set of models for evaluating a range of risks under stress, followed by both a quantitative or qualitative impact assessment of the outcomes, and commentary on remediation or strategic management responses. Whilst stress-testing “makes sense from a regulatory perspective,” it may also not be enough.

Kaminker explains: “As fiduciaries, we’re going to stress test anything that could be material. Consequently, we are stress testing our portfolios to understand how well they are positioned and where the risks might be.”

A coalition of the willing

The UK and French Banking regulators are among the first to require stress tests for climate change, running exploratory 30-year climate-change scenarios, set out by the Bank of England and Banque de France, respectively.

Using its own data and a bottom-up approach, the Bank of England’s Biennial Exploratory Scenario (BES) will test the resilience of the current business models of the financial system to climate risks. Quantifying the extent of potential climate-related disruption to balance sheets, the BES is expected to reveal the scale of adjustment required for resilience across the sector.

Across the Channel, the ACPR – the independent authority responsible for monitoring the conduct of French financial institutions - is also engaging in scenario analysis.

Reinforcing the need for a “bespoke approach based on transition scenarios”, Morgan Desprès, a senior official at the Bank of France and head of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), explains the role of the network in establishing the reference scenarios: “We worked with a scientific consortium to build scenarios, available for use by the financial services industry. These scenarios are a public good, so central banks and financial providers can use them in their own exercises. We’re trying to achieve a harmonised standard of measuring exposures following scenarios.”

Morgan Desprès, Bank of France

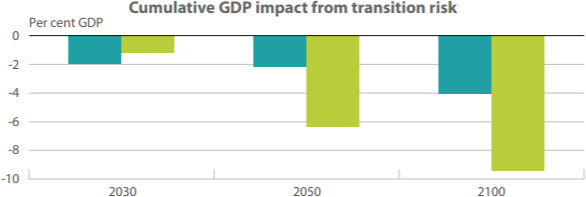

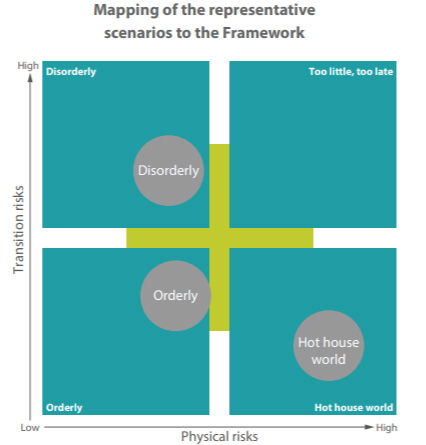

The NGFS proposed three scenarios based on the Representative Concentration Pathways estimates provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

- The first scenario sees a transition to a low carbon economy in an orderly and predictable manner. Commencing in 2020, temperature rise remains below 2°C and the structural transformation of the economy is announced, anticipated, and happens with little major macroeconomic shock;

- Scenario 2 sees a disorderly transition. Following insufficient action to maintain warming below 2°C by 2030, households and organisations must adjust their behaviour rapidly, leading to significant macroeconomic and sectoral disturbances, and

- Scenario 3 sees business as usual, and a hot house world. GHGs continue to rise and temperature surpasses 2°C. This final scenario translates into severe physical risks in both the medium and long term, however transitional risks remain limited.

Despite the progress, climate-related risk taxonomies remain heterogenous, and most financial institutions do not have the necessary tools to assess climate and environmental risks on their balance sheets.

Desprès says: “Our objective at the NGFS is to help each other. We aren’t a legal entity or an international organisation, we are just a platform that aims to share our experiences and knowledge. We all faced the same risks and challenges when it comes to measuring climate risk, so we decided to team up to be able to leapfrog the various steps that needed to be take. We are a coalition of the willing.”

The hardest part is how

Will alone, however, will not equip the financial sector with the ability to withstand the climate crisis.

Kaminker continues: “The hardest part about all of this is not the why, it is the how. How do you measure climate risk? How do you detect it? How do you stress test it? It isn’t straightforward. The methodologies are formative, so is the guidance from central banks. We decided not to wait for models and guidance to be developed, but build the capability in-house, because there is such a large investment opportunity here and it is so material. So that’s what we have done - built an implied temperature alignment model which provides us with a forward-looking data point. With our team of climate scientists, geospatial analysts, economist and more, we built a model that looks at 153 different industries and assesses pathways for each industry. It is regionalised, so we don’t compare Asia with Europe.

“The model gives us a new axis to compare companies on. Not only do we know their carbon footprint – how high they are flying – but we also know whether they have a parachute or not. We can look at high carbon industries and use this model to analyse and understand the extent of the issues, and how they may evolve over time. The TCFD produced a review and our model was included as the only asset manager temperature model, out of seven others. Ours is much more granular and digitalised than others. It is more thorough.”

Beyond temperature increases, Lombard Odier is also developing a geospatial model which maps physical asset locations and climate hazard models, using satellite imagery.

In line with Articles 2 and 3 of the Paris Agreement, “these models give us the ability to assess how exposed companies are to physical risks from climate change – heatwaves, storms, hurricanes, drought and wildfires,” Kaminker concludes.

Deployment of such a model would be invaluable in Texas or California, enabling authorities and institutions to identify risk to local infrastructure and other assets.

Assets on shaky ground

Indeed, assets all over the world are at risk from extreme weather and environmental hazards. The UK, which represents the third-largest property market globally, faces increased flood risk as all the data points to more frequent and intense bouts of rain.

Navigating the growing risk calls for asset-level risk-exposure assessment. For example, geospatial analysis, which maps asset locations and local data, can help investors and institutions identify high-risk assets.

Tom Backhouse, CEO and founder of Terra Firma, believes we have made impressive progress when it comes to mapping environmental risk, such as flood predictions.

Tom Backhouse, Terra Firma

Speaking to PBI, Backhouse says: “Ten years ago, most flood risk modelling was done on a consultancy basis. Now, banks and insurers have access to digital models instantly, which enables them to assess their losses now or in the future, under multiple scenarios. We want to achieve this with ground risk.”

Terra Firma is a British firm of geologists, engineers, and soil scientists who understand complex ground hazards, and their interactions with the built environment. Terra Firma partners with financial institutions to integrate risk assessment information into the real-estate investment process.

Tim Farewell, science and communications director at Terra Firma, explains: “We initially built the service up for homeowners, trying to integrate the risk assessment information into the process of buying property. We currently provide our advisory reports to roughly 1 in 10 transactions in England and Wales, but our target is to get everyone investing in real estate to access this information. We’re also providing a forward-looking risk model to banks, alongside other institutions, so they can access the information instantly.”

Tim Farewell, Terra Firma

Farewell adds: “When it comes to ground hazards – coastal erosion or clay swelling and shrinking - most of the information is still stuck in the literature or in people’s minds. There is an abundance of knowledge, but it hasn’t been digitised or manipulated so it can’t be provided to the individuals across the country whose real-estate assets are potentially at risk from ground hazards. Terra Firma’s mission is to modernise this knowledge, so we can help people, who aren’t geologists, make better decisions when it comes to investing in real-estate assets.”

According to Farewell, thousands of properties are ticking time bombs: “Investors ought to know that their property might not be there in 50 years because the coast is eroding so significantly. Many houses on the coast are fully mortgaged, they are insured, and people buy them because they are premium value. Except, they are a huge risk in a mortgage lifetime. On the Humber coast alone, there are 4,000 properties at risk. Wealthier properties are often more at risk because they are typically located in the more dramatic parts of the country, which pose greater ground hazards.”

Like the BES, Terra Firma works to guiding banks from understanding the risk in portfolios, to eventually integrating the information into its lending activities and other financial services. Backhouse concludes: “Banks must integrate this type of information into their decision making, which, in turn, will put the consumer first. The banks are now in the best position to dictate what is needed, and how to manage the risks.”

In 30 years, when the Humber Bridge begins to crumble, at least we can say that we saw it coming.