REGULATION

New MiFID rules risk damaging trust in ESG funds, experts fear

European proposals on ESG fund distribution are sparking worries about mis-selling, market fragmentation and, as a result, potentially reduced flows into such products – and MiFID is not helping either. Elizabeth Meager of Capital Monitor writes

N

ew European rules on sustainable finance that aim to give investors more say on their ESG preferences are in the pipeline.

An applaudable and sensible goal on the face of it, but national regulators, financial advisers and trade associations are worried about the complexity the plan would introduce to the fund sales process.

There are fears that the proposed changes to the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II) will confuse investors, risk product mis-selling – a particular concern for regulators – and make the cross-border distribution of funds more difficult.

That hardly fits with the ultimate goal of MiFID II: to protect investors and prevent mis-selling by setting standards of conduct for financial service providers.

The amendments form part of the EU's broader sustainable finance package, which includes the taxonomy regulation, disclosure regimes for asset managers and corporates, and several smaller amendments to other rules.

MiFID II changes

Proposed in late 2019, the MiFID II amendments have been adopted and are being reviewed by the European Parliament and Council. The market’s working assumption is that they will be adopted as they are, and that the supervisory authorities for banking, securities and insurance will provide further guidelines.

The MiFID II changes will mean that even financial advisers with no ESG expertise at all must consult clients on their sustainability preferences and incorporate those preferences into the advice they provide.

The European Commission had initially suggested offering clients funds classified as ‘light green’ or ‘dark green’ under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, but as Capital Monitor reported in May, that categorisation process is mired in confusion.

Policymakers have instead proposed a process by which advisers can determine suitability. But it assumes a level of ESG expertise that the average investor – and many advisers for that matter – does not possess, say regulators and advisers.

Market watchdogs are concerned about both mis-selling and fragmentation.

“We hear a lot of different debates about definitions and the types of funds being offered to clients that have stated an ESG preference,” says a national European regulator on condition of anonymity. “This concerns advice, which is very tangible. There’s a real mis-selling risk, as distributors need to know exactly how the categories are going to work. It’s essential to their job.”

A further concern is that the taxonomy – the most standardised framework on which advisers can base their advice – may be finalised after the amendment becomes effective, according to the slated time frame. Such sequencing issues are not unusual, but they will not make things any easier.

“We might not always agree with the technical standards and final rules, but the most important thing is that we have them, and that they’re consistent,” says Dominik Hatiar, a Brussels-based regulatory policy adviser at the European Fund and Asset Management Association.

Product distributors have similar worries.

“The concern is inconsistency of approach, and without a doubt I’d back that up. It’s not just regulators [who are] worried about greenwashing – we all are,” says Leslie Gent, head of responsible investing at UK private bank Coutts.

“When we look at the funds on our selection panel and how they’ve been classified, it’s not always clear why [such] decisions are made,” she adds. “You just can’t rely on that information alone, and it worries me that investors may be expected to.”

Regulators and advisers are ultimately concerned that these amendments will undercut two central objectives of the European project: preventing mis-selling, and creating a standardised, level playing field across EU markets.

Mis-selling risks

The conversation between a financial adviser and their client is called a suitability discussion, and in many instances ESG has long been part of it.

A typical suitability discussion – which often involves the client ticking boxes on an online form – covers the client’s risk appetite and desired returns. It might ask about their ethical values, such as preferences on exposure to sectors such as weapons, tobacco and to a lesser extent oil and gas. But in most cases, it stops there.

The new requirement will formalise those conversations and expect them to incorporate considerably more detail. Advisers will first need to educate the client on complex regulatory concepts, such as taxonomy alignment and ‘adverse impact’ indicators. Advisers must then present a number of options.

“There are so many different indicators, and it’s just not clear how the client is expected to respond to these options,” says Hatiar. “It also runs contrary to concepts like the ‘ecolabel’, which the [European] Commission says will make things simpler by guaranteeing that a product is best-in-class.”

Arguably, the proposals put the onus back onto investors to express an opinion on something they’re unlikely to know much about.

Arguably, the proposals put the onus back onto investors to express an opinion on something they’re unlikely to know much about. This is especially problematic because MiFID II’s suitability test was intended to safeguard retail investors against overly risky or complex products.

Owen Lysak, financial regulatory partner at legal practice Simpson Thacher & Bartlett in London, is seeing a greater focus on what exactly fund managers say to investors about ESG issues. This is in relation to both main fund documents and bespoke reporting arrangements.

“People want to make sure there’s nothing that could come across as misleading, or cutting across an investor’s expectations or ESG requirements,” he adds. “In a way, the MiFID change doesn’t massively move the dial on that concern from a fund manager’s perspective. But it’s clearly another marker of the mis-selling risk surrounding the ESG credentials of managers at the moment.”

The not-so-single market?

The MiFID proposals also raise the spectre of EU market fragmentation, an admittedly common theme in a bloc that comprises 27 nations with their own financial regulators.

“If a distributor isn’t willing to sell a fund because it doesn’t match their ESG classifications, [that creates] a very strong fragmentation risk,” says the anonymous national regulator. “That would make cross-border fund distribution impossible.”

The official says their watchdog would not rule out providing guidance if the European Commission were not forthcoming with its own. This is typically how fragmentation issues arise.

If the Spanish regulator, for instance, were to tell asset managers to classify their funds one way, but Luxembourg took a different approach, that would introduce a new regulatory risk and would likely prevent advisers from selling funds with different ESG classifications.

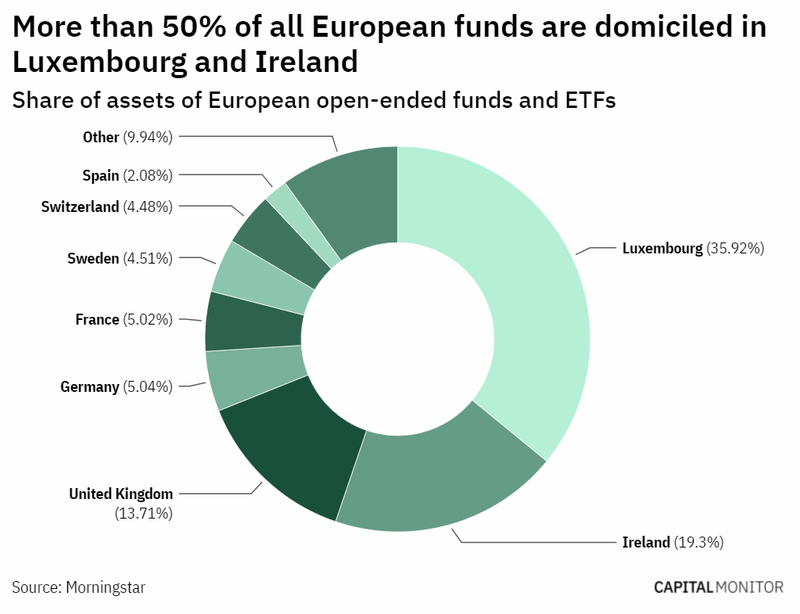

This matters because more than half of all European funds are domiciled in Ireland or Luxembourg to benefit from preferential tax treatment (see chart below). The EU has the highest concentration of cross-border funds in the world, with at least 3,000 registered as of December, according to PwC.

The issue is particularly acute for UK-based financial advisers. While the latter group is still subject to MiFID II under the Brexit withdrawal agreement, the ESG suitability update was not onshored, and they are now regulated independently of the EU. Consequently, there is speculation that the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) will introduce a similar, but more principles-based, requirement. An FCA spokesperson declined to comment.

The MiFID II proposals are ultimately adding to the mass of regulatory uncertainty surrounding ESG-related investment products.

The eventual fate of the sustainable finance taxonomy, which has been highly politicised, remains uncertain. There have also been considerable delays to the EC’s revised sustainable finance strategy, which is expected in July. All this reflects the nascent nature of this market and the lack of widely agreed standards.

Yet the commission will need to provide some form of clarity soon or it risks damaging confidence – and thus slowing investment – in ESG products.

For more information, check out Capital Monitor.